The Colville Indian Reservation land base covers 1.4 million acres or 2,100 square acres, located in North Central Washington. Colville Reservation lands are diverse with natural resources, including standing timber, streams, rivers, lakes, minerals, varied terrain, native plants, and wildlife.

The Reservation is occupied by over 5,000 residents, both Colville tribal members and their families and other non-Colville members, living either in small communities or in rural settings. Approximately half of the Confederated Colville Tribes’ membership live on or near the reservation.

Fatal crashes on the Colville Reservation, 2001-2009. Source: Fatality Analysis Reporting System, National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation

Our tribe found motor vehicle fatalities to be devastating and unacceptable, because they are largely preventable. We took action, including primary prevention measures such as re-engineering roads, and secondary prevention measures such as improving our EMS response and increasing seat belt and child safety seat use.

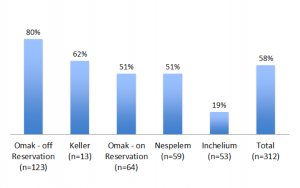

Implementing the Native CARS study was a good fit for us, timing-wise, and with our priorities and goals as a tribe. We conducted a baseline Native CARS survey in 2009 to find out how children were riding in vehicles. We found that 58% of children were properly restrained, but proper restraint varied widely by district.

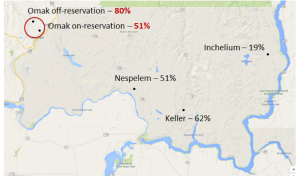

When you put it on a map, you can see how proper restraint varied across the reservation. The interesting thing about the town of Omak is that half the town is on the reservation, but when you cross the river, the other half of the town is off-reservation. We did vehicle observations on both sides of Omak, and this is what we found: On reservation, 51% of children were properly restrained, while off-reservation, where drivers are subject to Washington State law, 80% of children were properly restrained.

Children who were at increased risk for riding incorrectly restrained or unrestrained included booster seat age kids (age 4-7), kids traveling close to home, and kids riding in trucks.

When we asked about knowledge of the recommendations, drivers said they knew kids should be in booster seats until age 8 and in the back seat until age 13, because the Washington State law requires this. Awareness was not our primary issue. One of our strengths was that previous tribal outreach by a child passenger safety technician was successful. He distributed booster seats to those in need and provided community education. Though the program was no longer operating, people still talked about it.

When we asked about knowledge of the recommendations, drivers said they knew kids should be in booster seats until age 8 and in the back seat until age 13, because the Washington State law requires this. Awareness was not our primary issue. One of our strengths was that previous tribal outreach by a child passenger safety technician was successful. He distributed booster seats to those in need and provided community education. Though the program was no longer operating, people still talked about it.

Building from this success, we had four child passenger safety seat technicians trained – one for each district. The techs conducted car seat clinics, provided education through 20 modified Safe Native American Passenger (SNAP) trainings, and distributed 234 car seats in conjunction with the SNAP classes.

We also did a public awareness campaign. We created radio PSAs, posters, and billboards, and utilized social media to promote child safety seat use and increase awareness that CPS Techs were available to help.

A lasting victory for the Colville Native CARS project was the development and implementation of a primary tribal child passenger safety law. We had just updated our seat belt law, but our child passenger safety law was outdated and vague. The timing was right for us to address our child passenger safety policy.

Updating the law was a two year process that involved assessing community support for the law (98% of drivers surveyed said they would support a tribal child safety seat law), working with tribal attorneys and tribal council to draft a law, holding public hearings to listen to comments on the law, developing a police training program to facilitate enforcement of the law, and developing a diversion program that waives the fine for first time offenders who complete a child passenger safety training course. You can read more about how we passed the law in Module 11.

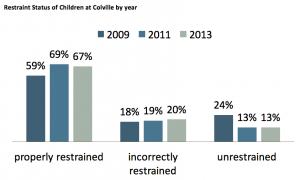

In 2011, after one year of collecting data and planning and one year of very active education, awareness, outreach, and policy work, we achieved a statistically significant increase in the percent of children riding properly restrained in vehicles. This increase was sustained two years later, after putting in significantly less time and resources toward child passenger safety activities. Importantly, we observed a decrease in the percent of children riding completely unrestrained from 24% in 2009 to 13% in 2011 and again in 2013. We also observed a statistically significant increase in properly restrained children traveling on reservation compared to no significant change in the off-reservation portion of Omak. This told us that we were reaching our target audience.

Some of the challenges we faced were covering a large area, keeping techs motivated, and choosing the right people to photograph for our media images. After we passed our tribal child passenger safety law, we had difficulty motivating police officers to enforce the law. We developed and implemented training for law enforcement officers to help address this.

The success of our program was largely due to collaboration. Within our tribe, we had Tribal Health, Tribal Police, and Target Zero on board. We also worked with the Washington State Traffic Safety Commission and the Washington State Safety Restraint Coalition. This kept us engaged in our efforts and helped us be aware of other resources and activities going on in our region. You can check out the videos we created as part of this collaboration here: http://wtsc.wa.gov/resources/videos-youtube-vimeo/